Hidden on the outskirts of the southern Chinese boomtown of Shenzhen lies a warren of narrow buildings that once produced two thirds of the world’s oil paintings. The suburb of Dafen – now officially named Dafen Oil Painting Village – grew in the late 1980s after Huang Jiang, an enterprising master art copier from Hong Kong, relocated his team of artists to the impoverished fishing village to take advantage of cheap rents and it’s proximity to international clients in Hong Kong. Over the years, demand for his knock-offs skyrocketed and many struggling artists chose to take up blue-collar jobs as commercial artists while art students flocked to Dafen to train to specialise in copying specific styles such as the Impressionists, Renaissance or Picasso.

At its peak, dozens of Dickensian studios employing Huang’s factory-like processes crowded the town. Individual workers each focused on a specific compositional element— eyes, flora, background detailing — dutifully painting their part and then passing the canvas along the chain. Business was more than good.

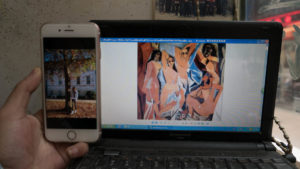

But Huang became a victim of his own success and, ironically, it proved just as easy to copy his business model as it was for him to copy Van Gogh’s Starry Night. His innovative methods to speed up production times quickly spread across the country and persist to this day. “If the order is for two to five pieces then one of us will do all of them,” says Justin Zhang, a painter at a factory in Yiwu, a town over two hours inland by high speed train from Shanghai infamous for its production of almost all Christmas decorations in the US. “For more than 50 pieces, a few of us will work together and each focus on a specific part in sequence. Only a handful of painters are skilled enough to do portraits or animals so most of us stick to abstract stuff as it is easier”. Legend still has it that Huang once produced 50,000 paintings in a month and a half for Wal-Mart, the US retail giant.

In the 90s the government started backing the burgeoning industry with the creation of dedicated production centres and a slew of incentives ranging from tax breaks to subsidised rents that led to an unprecedented period of profitability for commercial art in China. But that golden age has now waned with the decline in foreign demand for mass produced replicas and many factories are escaping the expensive urban hubs for more affordable rural locations. Questions remain about whether they they will be able to find new sources of income for their talents away from the old Orwellian production lines.

Up until recently, factory managers and painters were largely forced to rely on antiquated art brokers who were often the only link between the facilities and foreign customers and profited from the deep information inequality between the different parties. But the industry is undergoing yet another period of profound change that may finally benefit the many skilled artists of the country as they attempt to find a livelihood under the new paradigm. The advent of the internet paved the wave for smaller companies to sell directly to customers on the other side of the world through services like Instapainting.com. While many former factory artists have to find new work such as driving for Didi (Chinese Uber), online art commissioning services offer an alternative to the most talented artists by making it economical to deal with customers far away for higher priced single piece orders.

Chinese oil painting can trace its origins back to local artists who picked up the techniques from visiting Christian missionaries towards the end of the Qing dynasty. In the early 20th Century, Xu Beihong became one of the first artists to win acclaim for his ability to use oil paints. After the takeover by Communist forces, the Soviet Union would help popularise the art form while replicas garnered the moniker “Korean paintings” on account of the myriad shrewd Korean businessman who flooded in to turn a profit by exporting.

But the art form has a chequered past in the country and did not escape the attention of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution during the 60s and 70s. Art deemed “bourgeois” was outlawed and the government dictated that the only permissible art should be hóng, guāng, liàng, or “red, bright and shining.”

“1988 to 2000 was the peak of the copying industry,” says the owner of a factory in the city of Xiamen, who prefers to remain anonymous. “In those days, the internet was not well developed and mass production of famous paintings was our entire industry. In fact, two-thirds of our orders were signed with fake western names and the rest we left unsigned. Some customers, mainly galleries, would even require us to produce bogus biographies for those fake names.”

So common was the usage of fake names during the early boom years that artistic appropriation became a contentious issue and the wounds still fester to this day. Nianlen Chen now runs his own shop in Dafen village and says the practice of artists writing their names on art made from China is no different to stealing. “Most painting businesses exploit their staff,” Nianlen says. “I used to have to sell my paintings to a middleman who would then sell it on for much more. In those days, I would sign my name as ‘Antonio’ because it sounded Mediterranean. Everyone did it for the Western market.”

Down the road, Longhua Liu bristles in the knowledge that a renowned Parisian gallery is selling his work under a fabricated English name. “They shouldn’t be doing it but I understand it as a business strategy,” Longhua says. “Most people in Dafen are businessman but I am an artist.”

Since then, the slowing of the Chinese economy, higher labour costs and a government that no longer favours labour-intensive industries such as oil painting, has soured the mood for the thousands of artists in Dafen still toiling to reproduce famous paintings for the mass market. Beijing has placed innovation and technology at the centre of its new economic strategy as it shifts away from its decades-old growth model built around traditional manufacturing.

The metropolitan area of Shenzhen, in which Dafen is a suburb, has become China’s equivalent to Silicon Valley and now contains some of the most expensive real estate in the country. The changes have forced traditional art factories to flee to second and third tier cities as well as more rural areas. In Dafen, modern high rise condominiums now eerily line the outskirts of the village. Nearby, condo salesmen and the security guards at the neighbouring, and largely empty, art museum have developed a habit of barking at visitors they mistake for trespassers. With the global recession and oil painting production from China in a downturn, it seems everyone is less friendly here.

Nearby, one of the larger painting companies in the village has had to adapt to the requests for original designs. Despite the downturn, furniture superstores and big-box retailers from North America are still ordering large quantities of single paintings produced by their artists who work privately from secretive rooms scattered throughout the factory building. But these days, with such cut throat competition for a dwindling client base, each factory’s creative processes have become fiercely guarded. The owner is an artist himself and, while his personal work always sells for a premium, his factory churns out low-cost pieces that workers usually finish as they lie haphazardly strewn across the courtyard floor.

The mass oil painting industry extends beyond Dafen. Further up the Pearl River Delta lies the city of Dongguan, renowned for being the prostitution capital of China.Yet traditional manufacturing and vice are not the only industries in China’s city of sin. In the 1980s, over 2000 people worked as painters across the city. The painting trade only began to languish after Dafen started receiving government support instead of Dongguan.

Despite the decline, Dongguan’s second largest oil painting factory is still in operation and the stories of mass production are familiar. “Personally, my record is 400 replicas of a single painting,” says Li Li, an artist who has been working in Dongguan for 8 years and specialises in painting flowers. “I learned the basics of painting at a professional art school and then apprenticed with a master afterwards. When I was young, I used to love art and it was my only hobby but now it is just a job. I paint whatever the market needs but, frankly, I don’t do it in my free time anymore.”

Jianwen Wang, a specialist in impressionist and abstract copies, is less despondent. “I’ve been at the factory for 11 years and I don’t feel the work has become tiring,” he says. “Sometimes I have to work on boring paintings but most of the time I enjoy it. My record is several thousand replicas of one piece. In any case, it beats working in the iPhone factory down the road. When I’m not working on orders I’m painting my own stuff.”

Artistic quality and labour rights have become sensitive topics in this part of the world. “If foreigners don’t like our paintings then why do they keep buying from us?” continues Jianwen while glancing at an iPad next to his easel displaying today’s image to paint. “And I don’t feel oppressed…they say those things in order to lower our prices.” In China, a good artist can earn up to 7,000 yuan ($1000 USD) a month, over double what a factory worker will earn, although only slightly more than a regular office worker salary of around 5,000 yuan ($750 USD). The artists usually live far from the city centre where rents are lower but there are other benefits. “This job gives me way more free time and choices than a regular job,” says Yiyin Lin, a commercial artist in Xiamen. “I’ve sold some of the original paintings I made in my free time for up to 20,000 yuan ($3000 USD). As for foreign artists and resellers stealing my work, it happens much less now than it used to. Besides, it just means they are lazy. I’ve often heard that Americans look down on our art but I feel it’s all down to personal taste.”

Jingshan, Yiyin’s colleague, has a more nuanced opinion: “The quality of the painting depends on what it is used for and the ones I am doing are for commercial use so, yes, they will always be lower quality than the original works I do that I keep and sell to Chinese collectors. So perhaps it is fair that Americans say our art is bad!” In any case, many commercial artists are in it for the money and willfully turn a blind eye to the practice of appropriation even when they see their work on the internet blatantly selling under another name.

Back in Dafen, Maoming Zhu works as a painter at a factory and, although he prefers abstract or impressionist pieces, he mostly produces thousands of copies of the same painting and is relieved to not be working on the real factory lines. “Work here is totally different from working in the Apple factory,” he reveals. “Here I can walk around and I am relatively free.”

Xiamen, the other mass oil painting hub of China, lies half way up the coast to Shanghai where the South China Sea nears the East China Sea. Although the number of working artists in the region has declined since the halcyon days of the 90s, over 30,000 artists are still employed in the city’s painting industry. Here locals reminisce about the turn of the century, when the industry started producing more modern and impressionist art for changing consumer tastes. “I remember producing replicas of Marilyn Monroe for an entire year,” the owner of one Xiamen factory recalls. “After a period of time, the painter stopped needing to even use the reference image. In fact, I remember paintings of cowboys were the most popular request in those days.”

Inland from Xiamen city lies the town of Nan’an in rural Fujian province where Wal-Mart have stopped buying oil paintings from one factory altogether. “We ship 8,000 metal paintings a month to Wal-Mart,” reveals sales rep Leo Brown about their new product line using brushed metal. “These days we only export 4,000 oil painting replicas by container each month overall.”

The Nan’an factory is one of the largest oil painting and artwork production facilities in China and even offers art and drawing classes to children in the local community. The factory floor is filled with racks of mass-produced paintings, all done by hand.

Two hours drive north from Nan’an lies the smaller government subsidized oil painting town of Putian—one of the most rural in China. In a village on the outskirts of town, luxury cars look out of place parked in the narrow dirt roads designed for bicycles and motorbikes — residents only started buying cars five years ago — while the local river is choked with waste dumped by nearby shoe factories despite the government’s recent banning of the practice.

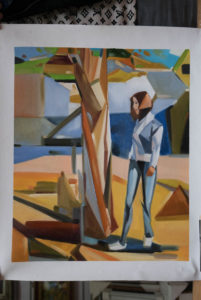

Many artists who work in the town of Putian live in the village, including Shaomin Zeng. He has been painting for almost 20 years and reflects on the cultural differences between the West and China: “Traditionally, oil paintings don’t come from China. Chinese people emphasize the content of the painting while Americans value the visual aesthetics so you can’t say which type of art is better”.

In this more rural locale, Shaomin has more freedom to control his own schedule and puts a positive spin on finding new ways to look at each replica he produces. He is a rare example of a commercial artist with the skill to produce photorealism and he charges up to seven times more for this. His most prized piece sold recently for 60,000 yuan ($9000 USD). “It takes me three to four hours to paint the face and hair for a 12″ by 16” painting, excluding paint drying time, and I always sign my name at the bottom. Photo to painting orders are relatively stable income and can provide enough for my basic living expenses,” he says.

Shaomin works with Instapainting through a local company that handles his customer interactions in English and packages and ships his completed works. Many of the artists from China work this way so they can focus on the painting aspect while someone else handles the business, logistics, and customer support.

Although replica Van Goghs continue to serve places like Dafen well — in 2015 revenues in the village were estimated to be 4.29 billion yuan ($630 million USD) as foreign art dealers continued to order copies of famous paintings by the container — the atmosphere has changed as the industry has moved away, exacerbated by the increasingly negative media attention that surrounds the purpose built village, the global recession, and increasing cost of living in the area. The end of the heyday for mass-produced Chinese art has resulted in the drastic downsizing of the industry and a pivot towards new product lines such as increasingly popular brushed metal art works or direct custom commissions (through sites like Instapainting.com). While the Chinese middle class may be growing rapidly, the shift from a volume-based model of selling cheap copies to businesses, to selling relatively more expensive original paintings to consumers, will mean that fewer artists and auxiliary staff will be sustained.

China’s migrant painters are most at risk and, in an era of internet enabled democratization of traditionally opaque industries, their livelihoods rest on being able to transition from the mass production of the past to new sources of painting jobs. Artists will be able to augment their dwindling traditional source of income with direct commissions through online custom art services like Instapainting.com and, in the vacuum left behind by the Chinese replica factories, an unprecedented opportunity is presenting itself for talented artists from across the world to finally compete.